Excavated and contaminated soil: a premium material for recycling

The need to preserve non-renewable mineral resources, whether from quarries or river and stream beds, is prompting construction firms to treat and decontaminate the soil excavated at their worksites with the aim of giving this premium material a second lease of life. Treating and reusing soil directly in situ prevents the excavated materials from being hauled away in trucks and thereby represents one step further in helping reduce carbon emissions from construction projects.

Excavated soil and sediment: what exactly are we talking about?

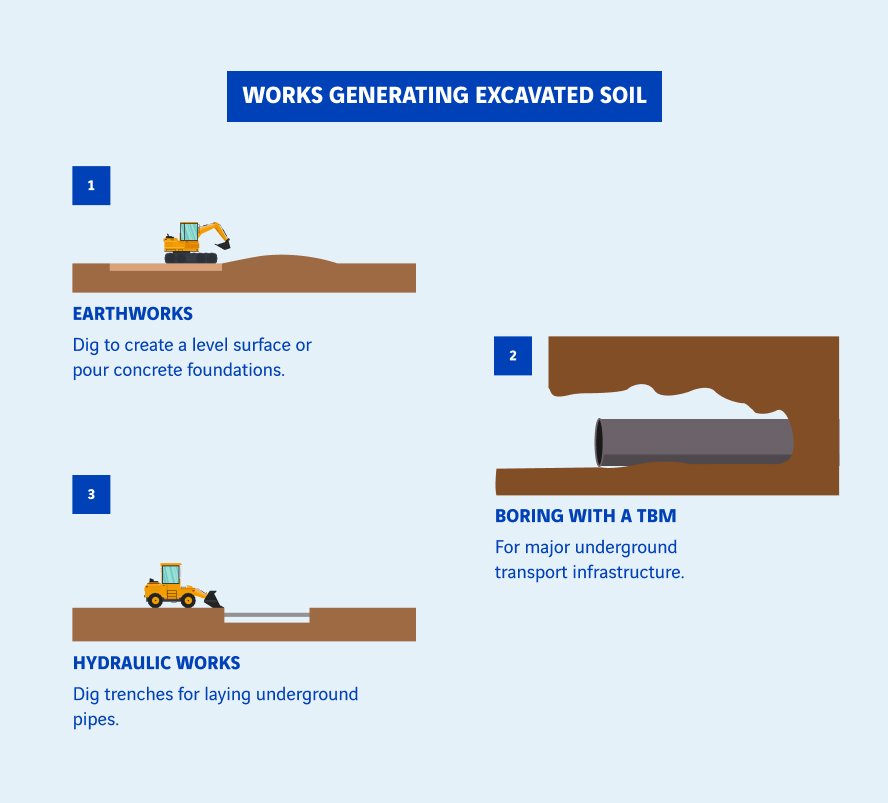

Excavated soil refers to the pre-existing layer of earth at the site, which is mainly removed so that civil engineering and construction works can be carried out. Various techniques can be used to excavate soil. Prime examples include earthworks, which involve digging into the earth to create a level surface or pouring concrete foundations, or digging with a tunnel boring machine when building major underground transport infrastructure. Soil may also be excavated during hydraulic works, where trenches are dug so that underground pipes can be laid. Excavated soil is not always contaminated. Everything depends on the site’s history. If the earth happens to be polluted, treatment processes are available for decontaminating the soil and therefore breathing new life into this precious material.

Excavated soil accounts for a substantial part of the waste produced around the world. In France, such spoil amounts to approximately 110 million tons every year, i.e. close to half of the 224 million tons of waste generated by France’s construction industry, which accounts for 69% of all the waste generated in the country (326 million tons). Sediment and dredge soil fall under the same category as excavated soil. They are produced when dredging ports, rivers and streams for the purpose of maintaining, re-establishing or developing navigability, preventing flooding or restoring ecosystem integrity. Every year, some 30 million tons of marine sediment and 1 million tons of continental sediment are dredged, which can also be recycled.

Over 200 million

tons of waste are produced by the construction industry in France.

Excavated soil: economic and logistical challenges…

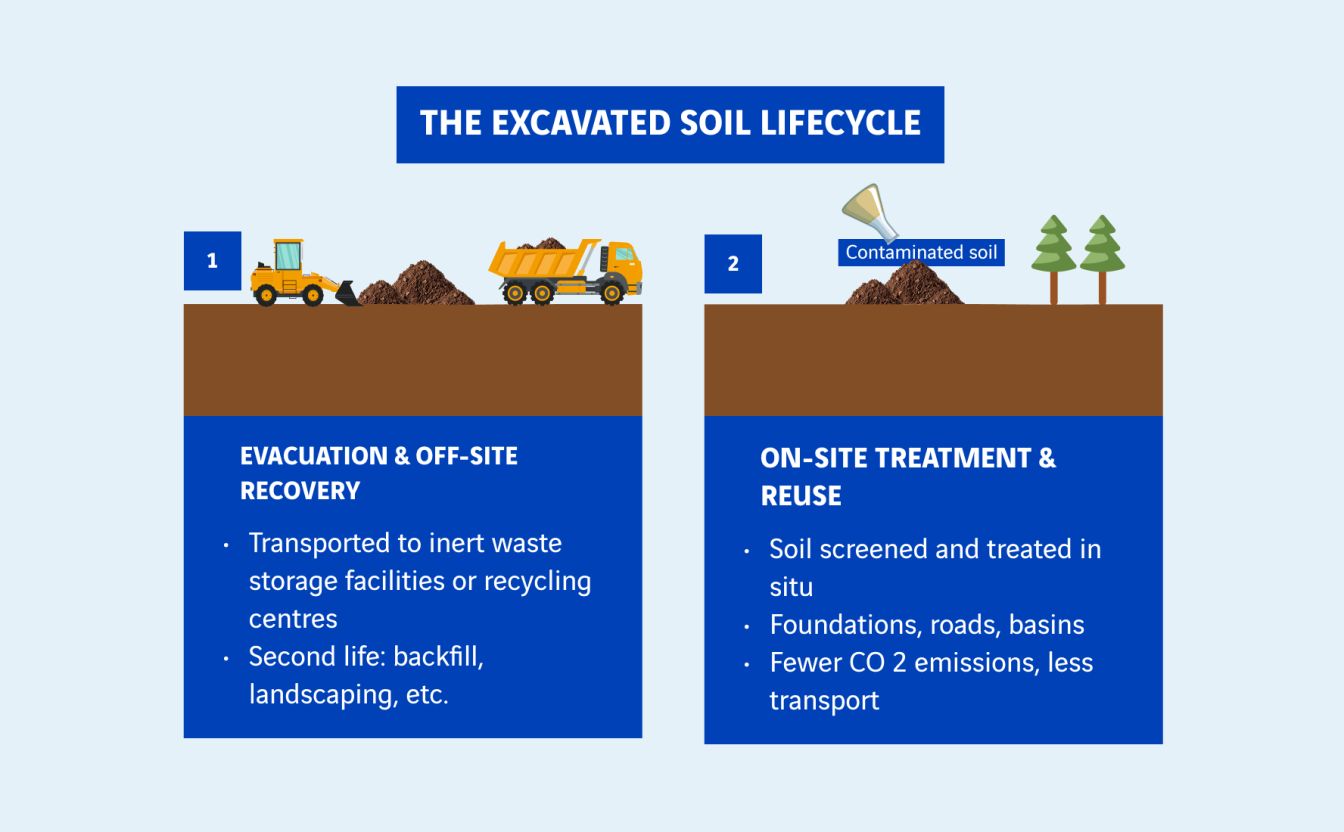

Most of the soil excavated at worksites is either carted away to storage sites (known as inert waste storage facilities) or transported to recycling centres so that it can be given a new lease of life. For example, it can be reused as backfill for landscaping and converting disused quarries into agricultural or leisure sites. It can also be treated and reused in situ, which has the upside of eliminating the carbon emissions caused by transport (whether trucks or barges), thereby shrinking the carbon footprint. Excavated soil poses a number of economic and logistical challenges, since treatment and road transport incur extra costs that weigh down on the economic and environmental performance of each construction or civil engineering project.

… and a non-renewable resource

Just like any other type of waste, excavated soil must be treated using a satisfactory process to avoid causing any harm to people and the environment. When sent to a landfill, it can start building up and saturating the centre’s storage capacities, and if it is reused without taking special precautions, it can pollute the environment. Excavated soil is a precious non-renewable resource, and volumes are set to rise, especially in light of the no net land take objective enshrined in France’s Climate and Resilience Act, which encourages developers to prioritise old brownfield sites. Whether pollution-free or decontaminated after treatment, such spoil is increasingly used to recreate ground surfaces, which helps cut down on the use of materials such as sand or rock from quarries, or sediment from streams and rivers, bearing in mind that these resources are available in limited quantities only and must therefore be preserved.

Characterising excavated soil to change its status from waste to resource

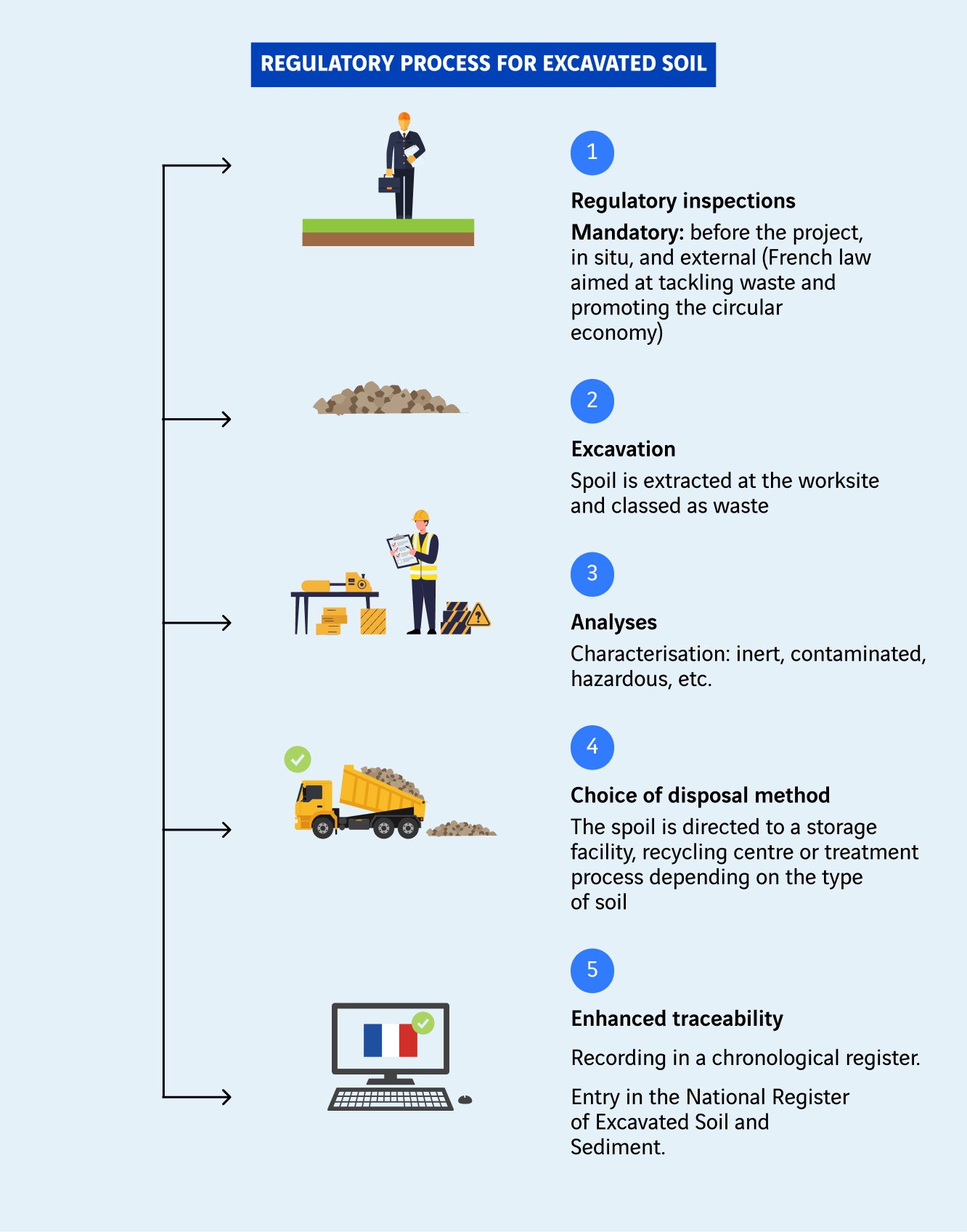

Excavated materials and soil are classed as waste as soon as they are removed from the worksite’s footprint. They are subject to restrictive regulations that require full traceability and a series of measures to respect the environment and biodiversity. Since they are considered to be waste, companies producing excavated materials must characterise them. Are they inert? Are they contaminated? Subsequently, they must find an appropriate disposal method according to the soil’s category once characterised, i.e. inert, non-inert, non-hazardous or hazardous. A traceability chain is then rolled out. These obligations were stepped up when France enacted a law aimed at tackling waste and promoting the circular economy on 10 February 2020, which introduced mandatory prior controls, in-situ checks and external inspections on excavated soil, while extending responsibility to encompass producers, storage centres, transporters and recycling facilities. In particular, the law requires all industry professionals to maintain a chronological record, while creating a National Register of Excavated Soil and Sediment. Excavation, transport, transit, trading, recycling and disposal activities must be tracked and entered in this national electronic register.

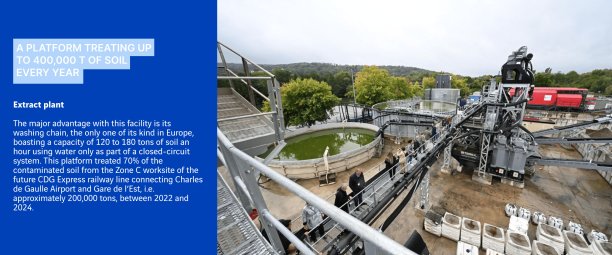

We recycle up to 95% of the soil and sediment received at the platform in Bruyères-sur-Oise (northern France).

Charles Tournemine, Operations Manager at Extract (VINCI Construction subsidiary).

We’re aiming to apply this recycling and reuse model to all the soil excavated at our worksites by 2030.

Jérôme Aubry, Technical Director of Sogea Environnement (VINCI Construction subsidiary).

Since excavated soil is classed as waste, producers are also required to adopt recycling principles. A lot of excavated soil still ends up in inert waste storage facilities or is used to fill quarries or implemented as backfill during roadworks, which is not classed as recycling but as disposal. However, the number of recovery and recycling methods is on the rise with the goal of giving the soil a second lease of life for rehabilitating land surfaces when redeveloping brownfield sites into housing estates.

Asebestos-free soil used for landscaping

To redevelop the longstanding brownfiel site of Résurgat 1 in Boulogne-sur-mer (northern France), Navarra TS, a VINCI Construction subsidiary, treated a total volume of 60,000 cu. meters of materials across a 15-hectare surface area. A wet screening process xas used for some of the spoil, which helps remove any asbestos detedted during the diagnostics phase. Sorting, removal and preliminary treatment operations were performed on site, which allowed the ast majority of excavated soil to be used in rebuilding the site's ground surface. The ground was reconstructed while taking steps to preserve biodiversity dur to the presence of various protected animal (seagulls and lizards) and plant spiecies, including wild orchids, as well as other invasive species.

Excavated soil can also be sorted to extract sand and aggregates that can be used in the composition of certain building materials, thereby saving valuable primary components.

Sediment recycled as beach sand

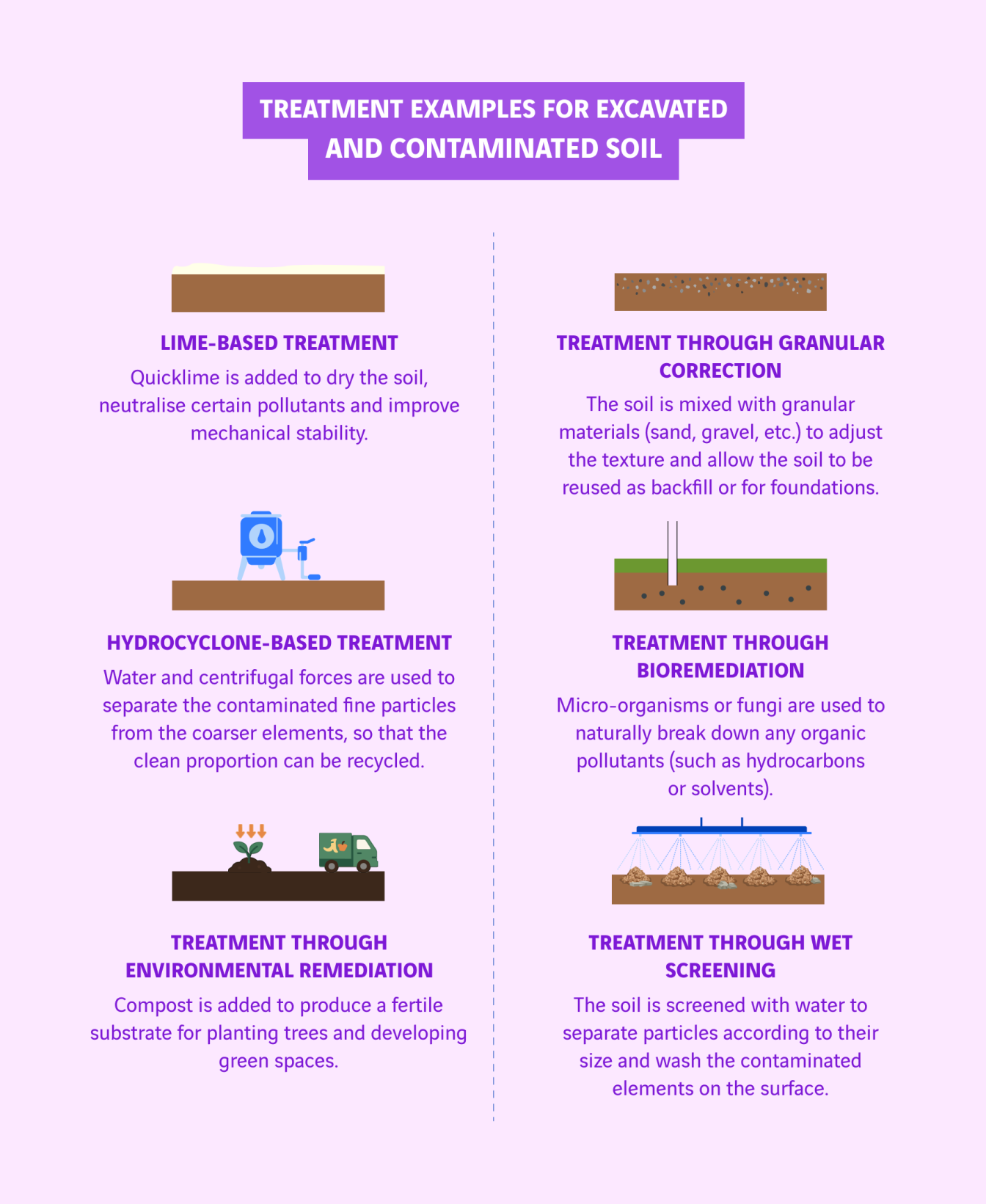

The dredging operations carried out in Port-Camargue carried out by Extract - a top tier player in sediment and soil treatment sector -, and Océlian, both VINCI Construction subsidiaries, resulted in the extraction of 5,000 cu. meters of materials in the port's south channel. The sediment was screened to remove the macro-waste and then subjected to hydrocuclone treatment to separate the fine particules and sand. Once washed, the sand was reused to top up the local beaches, while fine particles were dehydrated wit geosynthetic tbues and recycled as road sub-base materials.

Also, thanks to treatments involving the addition of lime or granular materials (granular corrections), soils can be turned into excellent backfill material. In the Velaine-en-Haye region (Meurthe-et-Moselle), for example, Sogea Environnement (VINCI Construction) is laying a pipe in a 1.5 km deep trench. The teams opted for a mobile unit that enabled the excavated soil to be treated in situ by granular correction, i.e. by adding granular material to the soil to restore its pre-extraction density and enable it to be reused as backfill without risk of subsidence.

Remea Polski is a VINCI Construction business unit specilised in environmental decontamination, soil rehabilitation and groundwater remediation, and has led several of the most ambitious decontamination projects that Poland has ever seen. When it came to rehabilitating the Kalina pond in the south of the country, the company used a thermal desorption method (extracting the water contained in a substrate, representing a first in Poland) to neutralise the chemical pollutants in the sedimentary deposits.

Finally, when excavated soil is taken from quality agricultural land, it can be subjected to “remediation” treatment, which involves adding compost to transform the soil into a fertile substrate, which can then be used for planting trees and developing green spaces. Once extracted and crushed, millstone can be used for landscaping, such as by creating gabion walls, comprising metal cages filled with blocks of stone.

Recovering excavated soil has a major role to play in achieving the objective set out in France’s Energy Transition for Green Growth Act of 17 August 2015, i.e. recycle 70% of the waste generated by the construction sector by 2025.

Sources :

- Sustainable Development Commission (CGDD), 2018

- https://www.notre-environnement.gouv.fr/themes/economie/les-dechets-ressources/article/production-de-dechets-comparaison-europeenne

Subscribe

Stay tuned : receive our newsletter

Every quarter, discover new articles, exclusive features and experts' views delivered straight to your inbox.

Most viewed

Explore more

Marina Lévy - Companies at the heart of ocean conservation issues

Marina Lévy, oceanographer, research director at the CNRS and ocean advisor to the president of the French National Research…

Access to water in Africa: persistent challenges despite major progress

When looking at the situation of safely managed water supplies in Africa, the glass could be seen as half full, rather than…

Building with and for nature

Whether creating barrages, stripping away topsoil, cutting down trees or digging channels, humans have spent thousands of…